Newsroom

Empowering Youth Through Media Production, Mobile App Creation

A Few Moments with Lissa Soep

Since 1992, Youth Radio has been supporting youth-adult collaboration through joint media production, and as the organization’s Senior Producer and Research Director, Lissa Soep works daily with youth in producing credible, poignant broadcast and digital media content for consumer audiences. In 2010, Lissa co-authored Drop That Knowledge, which gives readers a first-hand look into the Peabody Award-winning youth-driven program. That same year, the Mobile Action Lab project, for which she served as principal investigator, was a winning entry in the third annual Digital Media and Learning Competition. What began as an innate appreciation for the art and craft of storytelling has evolved into a unique career that encompasses both theory and practice. We caught up with Lissa to discuss how Youth Radio’s media production process has changed in an age of participatory culture.

What’s behind the success of Youth Radio’s journalism education model?

Speaking from an education point of view, it really stems from two main factors, the first being our peer education model and the second a concept Vivian Chávez — a Youth Radio graduate — and I describe as collegial pedagogy. When they first enter the program, young people are really learning from others close to their same age who have recently gone through Youth Radio and are now in a position to be teaching media production. Then there are key points in the students’ development when collaboration and direct collegiality with professionals kicks in. This is really crucial in getting to high production values and big audiences for the content they are generating and the apps they are developing. We want the deepest participation in digital culture for young people. It’s in some ways the highest aspiration in terms of what participation can look like. Of course the first step is to provide experiences where young people learn how to use existing tools in interesting, nuanced ways. But we’re not just training young people to deploy existing technologies or social media platforms. We’re enabling them,

through partnership with professionals, to actually create new platforms for themselves and their peers.

through partnership with professionals, to actually create new platforms for themselves and their peers.

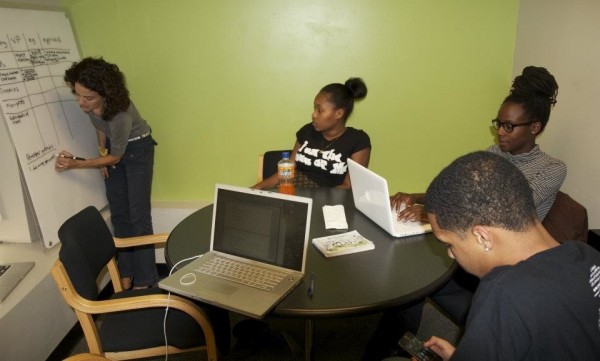

The model of collegial pedagogy grows out of Youth Radio’s newsroom, where young people have, as everyday colleagues, professional journalists from some of the biggest outlets in public media and commercial media worlds who bring that level of experience to the process of collaboratively developing media content. Together young people and adults are sharing their sources and figuring out how they will conduct fact checking, how they can best tell the story, and how it will be presented to audiences. It is an extraordinary opportunity not just for the youth, but for adults who don’t necessarily have access to young voices and insights.

What does this collegial pedagogy look like in a digital space?

It used to be, not long ago, that at the point a story was delivered, our work was pretty much done. Sure there were always email responses or some impact of the broadcast, but the culmination of the arc of production was when the content aired. Now that the material goes out into digital outlets, and as a result of social media, user generated content, and Henry Jenkins’ notion of “spreadable media,” there is this phase of production that happens after the story is delivered, after it has hit an audience, and once it starts circulating. It can be described essentially as the “digital afterlife” of young people’s content. There’s a point when people start linking to it, when we start to see comment chains form and when people start to make use of the content in ways that the original author may never have expected or intended it to be used. That very much becomes part of the production process, in the sense that the young people are constantly having to anticipate how the material is going to start to circulate and change hands once it’s been published.

This is a reality, and we must support young people as they ask themselves complex questions such as, at what point do I speak up in a comment stream? How do I track the way the story travels? Who is linking to it? How is it being reframed by other publishers once it starts moving in that digital afterlife phase? It’s very much deepened the training we have to provide and the learning we have to do on the fly as we, alongside the young people, have entered this new phase of what digital publication entails.

How has social media impacted the investigative reporting process for those in the program?

Social media isn’t just an engine of spread after the fact. It’s a way of finding sources, tracking information, and it aids in story topic identification. The gold standard here is that social media is playing a crucial role from the reporting phase to the distribution of the piece.

This is seen in our navy abuse story, a case where one of our reporters, Rachel Krantz, covered a Prop 8 rally and met a young vet named Joseph Christopher Rocha who told her the story of his abuse while he was deployed as a teenager in Bahrain, in the canine unit with the U.S. navy.

When it came time to track down the unit’s chief petty officer, we were having a really hard time going through official navy channels to get anybody to divulge where he was, or what his rank was. Both pieces of information were crucial in our reporting of the story, because we needed to make every attempt to give him a chance to respond, and we needed to verify that he had been promoted even after the abuse had been reported. In another interview of Rachel’s, someone mentioned a social networking site for military communities. It turned out that this chief petty officer had a profile within the site, which named where he was stationed and his ranking. That alone wouldn’t, of course, be enough as verification, but it gave us something to go on that we could then leverage as we continued to go through the official channels. Social media can be a mechanism for getting to the truth, and it really changed the nature of the experience for both the reporting team and those whose lives were being described in the story.

How does Youth Radio support young reporters in transitioning from media content producer to a more civically engaged citizen and employee?

Youth Radio is an organization that is very intentional in trying to create pathways from the learning experiences that happen here to formal education and career. Every young person that comes through the building works with a team of people in our college and career department who develop a customized action plan to help get the kind of support youth need to get where they want to go. Likewise, there’s a lot of opportunities for young people to participate in professional development training. We make sure that young people are supported in translating and hopefully converting work that happens inside this building and making it visible to potential brokers of opportunity outside, whether it’s for higher education or for work.

When I look at how that transformation actually happens, in the day-to-day work that we do, a good example comes out of our Mobile Action Lab, where we are supporting young people in learning to create new digital platforms. For our Forage City app, we partnered with Asiya Wadud, a woman from North Oakland who created a wonderful but labor-intensive food bartering system to gather and redistribute produce that would otherwise rot and go to waste. We wanted the app to capture the best parts of her project and make sure that that produce wasn’t just getting circulated within closed networks but was reaching people who wouldn’t otherwise have access to free and fresh fruit in their neighborhoods. A young colleague of mine, Rashawn Moore, has an abiding interest in food distribution and food equity and has taken an important leadership role in the energy behind Forage City. In my mind he has made that transition from being someone who is interested in that field and working in that field to someone who is collaborating with peers and colleagues to create an innovative new tool that didn’t exist before. Through his network, he has put us in touch with important potential partners in the Bay Area who could serve as our launch partners for Forage City, which is currently in the closed beta phase. He’s going out and scheduling meetings and trying to make the right people aware of what we’re trying to do so the app can make a real intervention in terms of food equity in the Bay Area and beyond.

So he’s really serving a community need?

We have always defined the Mobile Action Lab mission as young people partnering with professional developers to create mobile apps that serve community needs, but I’ve recently been influenced by Warren Sack from UC Santa Cruz, who talks about a shift in design from a user-driven design approach to a citizen-driven design approach. I have tried to push that even further from citizen-driven design to citizenship-driven design. What we are really after is creating technology that is both a product of activated citizenship, and then it generates and deepens and creates better momentum behind citizenship activities that are happening in communities. If we start with a community need, the message is something is broken here and we are going to create technology that fixes it, as opposed to when I look at our portfolio of apps, in many cases what we do is we notice activities within a community where there is already something brewing and something interesting going on. We want to create an application that makes a stronger, greater impact. That slight semantic shift has been helpful for me in terms of thinking about how we position the type of contribution we are trying to make now and in the future.

You first started volunteering at Youth Radio while writing your doctoral dissertation in education. What prompted you to stay?

I spent several years in the back of the room studying young artists as they created really interesting work in community-based sites, and my job was to take notes and record and analyze their discourse. I kind of hit a wall at one point and thought, wait, I want to be a part of this conversation. When I listened to the tapes and did the discourse analysis, I had this urge to join a creative effort. I also had a bit of journalism envy, and I thought, wow, these reporters are telling stories, reaching huge audiences and really in some cases shifting public assumptions and understandings. I wanted to be a part of that creative process of storytelling with youth. I have a background in visual art, and I wanted to remember what it was like to really be about that craft.

I thought about my career and became committed to this idea that maybe I could do work that combines research and scholarship, which was still a big part of my life, with hands-on media production with youth. I felt like when I was at Youth Radio, that’s what I was watching happen. People were about that creative narrative and were working with young people in a really collaborative way. And I don’t want to glorify that structure because there are plenty of times when I think tensions arise in that adult-peer dynamic, but to be able to work with young people who are not recognized as they should be as sources of authority — as storytellers whose material needs to reach big audiences — is really important to me.

Banner and secondary image: Courtesy of Lissa Soep, Youth Radio