Newsroom

Youth and Participatory Politics in a Digital Age

A Few Moments with Joseph Kahne and Cathy Cohen

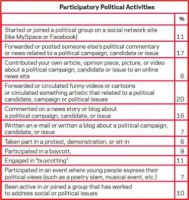

On June 26, the MacArthur Research Network on Youth and Participatory Politics (YPP), under the direction of co-principal investigators Cathy J. Cohen and Joseph Kahne, released the largest nationally representative study of its kind on new media, politics, and youth. The study, Participatory Politics: New Media and Youth Political Action, which surveyed nearly 3,000 young people between the ages of 15-25, shows that substantial numbers of young people from diverse racial and ethnic groups across the nation are engaging in “participatory politics.” We spent a few minutes with Kahne and Cohen discussing the implications of the study’s findings on the upcoming 2012 presidential election, education, and the country’s future political landscape.

Kahne is the John and Martha Davidson Professor of Education at Mills College. His research focuses on ways school practices and new media influence youth civic and political development.

Cohen is the David and Mary Winton Green Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago. She is the founder of the Black Youth Project and author of The Boundaries of Blackness and Democracy Remixed. Her research focuses on political engagement by marginal communities.

84% of young people surveyed said they would benefit from learning how to judge whether online information was trustworthy, yet media literacy continues to be a low priority on school agendas. What does this mean for democracy if these issues are not addressed in the very near future?

Kahne: While the question we asked was about judging the credibility of online content, it speaks to a broader concern. If we want people to produce thoughtful and strategic content or to circulate that content effectively to have impact, we need media literacy both around consumption, things such as judging credibility, as well as around the production that young people can do.

We can’t just assume that since youth can tweet and text that they know how to effectively leverage the power of new media to advance their interests and their priorities politically. When 84% of young people are saying they need help learning to judge the trustworthiness of online information, it is clear that there is a real need for educators in school and in out-of-school settings to focus on these issues.

Information is good for democracy and misinformation is bad for democracy. That oversimplifies it, but the stakes are high. It’s very hard to make good choices when you don’t have trustworthy information. In addition, when one is confronted with information and can’t tell if it is credible or not, there is an understandable drop in confidence that one should even be engaged.

With education policy shifting slowly, what steps can be taken now to jumpstart media literacy initiatives?

Cohen: One of the things we point to is the disparity in opportunities for young people to learn or have a valid civic education. We want to be cautious about locating all media literacy initiatives in schools. From Joe’s work with Ellen Middaugh, we know that young people from higher income schools have more opportunities for a lively civic education. There are after-school programs and new initiatives outside of schools such as YOUmedia in Chicago that provide a separate space where young people, through a very participatory model, can come together with mentors who support groups of young people to learn new skills and gain greater confidence in their use of new media.

Kahne: It’s very important to highlight that these extra curricular organizations, particularly organizations that target groups that are generally less engaged, can play a very valuable role. In schools, vibrant civic education is less common for some groups of youth than for others, which leads to inequitable engagement. In an earlier study with the Pew Internet and American Life Project, we looked at video games that had civic education opportunities embedded in them. We found that there were no differences across social class or race and ethnicity with respect to the likelihood that a young person would choose to play a game with civic learning opportunities. So these online opportunities can be a valuable and in some respects more equitable way to distribute these learning opportunities.

Participatory politics can allow for greater creativity and voice, but voice may not necessarily lead to influence. What sort of shift must occur in order for these practices to become influential?

Kahne: We have thought about this a lot, and it’s something we as a field need to learn more about. There is no doubt that practices that amplify the voice of young people are a significant thing, especially given the marginal status that so many young people have in relation to mainstream institutions. Those institutions are places where young people generally don’t have significant voice. Participatory politics can give them that voice. At the same time, it’s key to realize that if youth are circulating ideas among their networks without understanding how to move from voice to influence, they may well not achieve the goals they value. In our work with youth organizations, digital platforms, and youth themselves, we have to find ways to help youth connect to institutions act strategically to have influence and to put pressure on the places – whether corporate or governmental – to prompt the change youth want to see occur.

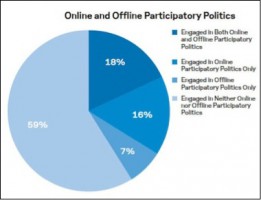

Cohen: Participatory politics is never meant to displace a focus on institutional politics. We might think of it as a supplemental domain where young people can take part in a dialogue about the issues that matter, think about strategies of mobilization, and do some of that mobilizing collectively online. That said, we have to always recognize that there is important power that exists largely offline. The Occupy movement is a classic example of both participatory politics and offline institutional politics coming together to not only amplify voice but also provide influence and power — even temporarily — for a group of primarily young people around class and equality issues.

Kahne: Many people assume or worry that youth who are getting involved in participatory politics may be doing it because of their dissatisfaction and disinterest in institutional politics. There is a fear that youth may be turning to these mechanisms for voice and neglect other important activities like voting. What we found was quite the opposite. Those who were engaging in participatory politics were twice as likely to report that they had voted in 2010 as those who hadn’t engaged in participatory politics. We don’t get the sense that youth who partake in participatory politics are neglecting more institutional pathways to influence.

Through participatory politics, these new media provide a lot of powerful ways for young people to exert both voice and influence. If we tap that opportunity and leverage that potential we can address what is currently a major concern, which is that many young people are largely disengaged from the political process, and we could increase their engagement quite significantly.

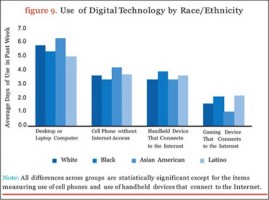

While the difference in voting in 2008 between the highest voter turnout (black youth, 52%) and the group with the lowest rate of turnout (Latino youth, 27%) is 25 percentage points, participatory politics are equitably distributed across different racial and ethnic groups. What impact do you foresee participatory politics having on these voting numbers?

Cohen: Racial and ethnic inequality has largely defined United States politics. If you look at the history of voting — the struggle for voting rights, the attempts to mobilize people of color and young people in 2008, and now the response of tightening registration laws in certain states and voter suppression — it’s clear there has always been a history of racial and ethnic disparity in terms of voting and other forms of institutional politics.

What’s amazing about the equity we see in participatory politics is that it takes certain barriers off the table. It’s excitin

g and important that there is a realm of politics that is largely free of some historical barriers, such as citizenship. In the realm of participatory politics one does not have to be a citizen to participate. That said, we are not suggesting that there are no obstacles in participatory politics realm. For example, for a really long time, people pointed to the digital divide as an obstacle. However the data that we have suggests that in terms of access to the internet, nearly every young person we interviewed found a way to access the internet.

g and important that there is a realm of politics that is largely free of some historical barriers, such as citizenship. In the realm of participatory politics one does not have to be a citizen to participate. That said, we are not suggesting that there are no obstacles in participatory politics realm. For example, for a really long time, people pointed to the digital divide as an obstacle. However the data that we have suggests that in terms of access to the internet, nearly every young person we interviewed found a way to access the internet.

Participatory politics can also impact or facilitate institutional forms of engagement like voting by providing something we call digital social capital. One can use new media platforms to search for information about the issues that they care most about. It’s much easier to access information by doing a search online. Similarly, discussion with others online can also help inform people and generate excitement around an election. Young people can find out online and through new media where their allowed to vote. They are also often embedded in networks where people are talking about the importance of the election, so one is mobilized to vote through those collectivities.

The equitable distribution of engagement in participatory politics is a critical model in terms of what we want to see in our democracy. It has a lot of positive spillover effects for the opportunity to vote in 2012. In this election year, we are going to see more and more young people finding campaign information largely online through new media. We are going to see young people engaging in campaign politics using participatory acts such as starting a group online or circulating political information among their networks. We are already seeing community groups and national groups using digital media platforms to provide information about the election as well as registration restrictions such as what type of ID you need to register to vote. We saw the significance of new media play out in 2008, and in 2012 we will see again with multiple entities using online and participatory political acts to get young people involved in the election and to the polls.

From a research standpoint, is it difficult to keep up with such a rapidly changing field?

Kahne: There’s no doubt it is challenging, especially if one is focused on particular platforms. In many respects that would be a mistake because those are constantly evolving. The relevance of MySpace, for example, can change quickly. Twitter didn’t even exist a few years ago. It’s more important for us to focus on broader dynamics and practices in relation to these media than on specific technologies.

Cohen: It also forces some choices in regards to form. In the old academic model, you gathered your data for a year, played with it for another year, wrote a book in the third year, and released a book the year after that. The whole process took five years. Now, you have to be quicker. Now we produce different types of products that are meant to be more interactive, and there’s recognition that what we find today may not be applicable to next year’s survey. And that’s OK. It’s just part of the excitement of doing this work.

—

The YPP Survey Project released findings from its national survey on new media and politics among youth on June 26, 2012.

Link: Executive Summary

Link: Key Data

Link: Full Report

Banner image credit: Cell Phone Freedom by Nicolas Will

http://www.flickr.com/photos/numb3r/2402267054/

Charts and graphs: Courtesy of Youth & Participatory Politics