Newsroom

Seeing Games as a Vital Part of 21st Century Literacy and Assessment

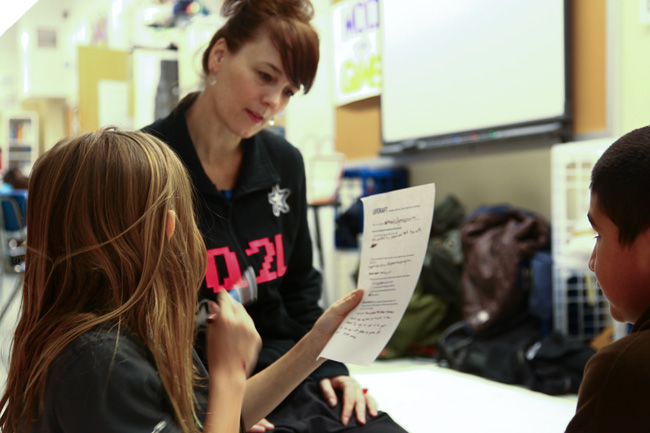

A Few Moments with Katie Salen

Known as an established game designer and design educator, Katie Salen is a go-to expert in the field of games and learning. Salen was the original lead designer of Gamestar Mechanic, a popular game making tool for youth which focuses primarily on game design, and she serves as Executive Director of the Institute of Play, a non-profit design studio dedicated to promoting game design and game-like learning. In 2009, Salen launched the non-profit’s first project, Quest to Learn (Q2L), an innovative New York City public school whose mission is to translate game-like learning principles into a powerful pedagogical model. This past June, the Institute of Play unveiled its latest project, Games, Learning and Assessment Lab, or GlassLab, which was launched with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Electronic Arts (EA), and the Entertainment Software Association (ESA). Housed on Electronic Arts’ Redwood City campus, the project is a unique research and development effort that aims to create game-based tools and leverage existing digital games to validate student learning of core skills identified by states for college and career success. We spent a few moments speaking with Salen about the Institute of Play’s evolution and how the video game industry is taking on a key stakeholder role in the education sector.

What kind of impact has Q2L’s curriculum had on students these last three years?

At Q2L, students have opportunities to explore the things they are most interested in with other students. The students have the ability to become experts in a whole range of things, which allows them to show leadership in the classroom.

One student in particular came from a really great elementary school, but already by 5th grade he was feeling very disengaged and very disconnected from school. He came to Q2L in the 6th grade, and his parents have remarked again and again on how he has blossomed socially. He’s a whole new kid. He has unusual interests, but Q2L’s collaborative and peer-based learning environment has enabled him to find a peer group. Because the school is set up in a way that allows kids to learn and interact in different settings that embrace creativity, he has become one of the leaders at school. He had good academics before, which have continued, but the social and civic dimensions of his character have really grown.

We have another child who came in as a very quiet, reserved student. This summer, we started to notice posts from the student on our social network site, QLink. The student decided to wage a campaign on behalf of a man in New York City whom he had befriended after engaging with him on a daily basis for quite some time. The man’s newspaper stand was in danger of being shut down because he did not have the correct permits, and the student used the social network to gather hundreds of signatures from students and teachers. That kind of civic engagement is really powerful to see in a young person of his age, and is a type of activity he probably wouldn’t have been engaged in when he first came to the school.

How did the idea to create a games assessment lab with Electronic Arts come about?

We had been doing work in broad learning contexts both through school and after-school programs for a few years, and the question of assessment always came up. We know from the history of innovation in progressive education that it doesn’t matter if you’re innovating around what learning looks like if you’re not also innovating around what the assessments look like. Students shouldn’t just learn to meet common core and state standards—that’s a great body of knowledge they should learn—but there’s a whole set of other 21st century skills students should be learning as well including complex problem solving, collaboration, and empathy. Teachers might develop a curriculum to include those competencies, but traditional assessments don’t measure them. If you can’t measure and provide evidence of learning, ultimately those skills won’t count in the context of school. We felt it was time to contribute to tackling the design space of what new kinds of assessments could look like.

We were most interested in asking questions about developing assessments within game environments. This is because games link together learning and assessment, are data-rich in that they can be instrumented to provide feedback not just for teachers but for students, and are designed to be engaging. One of the most important parts of GlassLab is the research work being done by SRI to validate the assessments we create, so that they might be offered as alternatives to more traditional forms of formative assessments.

One thing that is fairly unique about that lab is that we are thinking about the design of game-based assessment from a game modification or adaptation standpoint. Rather than starting from scratch we have the opportunity to modify existing commercial games and build into the robust technology that underlie them. For example, in addition to donating space, our partner Electronic Arts is donating intellectual property. So we will be working initially with a set of existing games that have already proven to be commercially viable and are really well designed, and start to think about ways we can modify them to bring in a more explicit learning and assessment dimension.

What does this new partnership with the video game industry mean for DML?

Over the years, there’s been an open dialogue amongst stakeholders around assessment and learning, but the video game industry has been on the peripheral of that conversation. My theory is that many video game groups—Games for Change, Games for Health—created (for many very good reasons) a didactic relationship of sorts from the very beginning—“games for entertainment” vs “games for social impact.” As a result, the video game industry, which tended to fall into the games for entertainment category, stood outside of the conversation around education and learning for many, many years.

EA and Valve, although Valve is not formally involved with us, stepped up to the plate last year and examined what it would mean to do work in the learning and education sector based on best practices within their industry. There has always been a wonderful reciprocal relationship between game companies and their players, and because of that relationship, they have a way of thinking about developing software for learning that might be very different from what it has looked like in the past.

Additionally, the video game industry as a whole is aging. It used to be that the industry was filled with young guys in their mid-20s, but now those developers and designers are getting older and having families. They are starting to wonder how their expertise as game developers might contribute to their children’s education. There seems to be a kind of culture shift happening because priorities have started to shift. A whole group of people who haven’t been part of the conversation in the past are now deeply interested in finding ways to become involved. It is really exciting just to imagine the expertise the learning community now has to draw on.

Was this path the Institute of Play has taken intentional from the very beginning?

We started as a tiny little idea back in 2007. We knew there was interesting stuff happening with the potential of games, but some of our ideas were difficult to explore in a commercial game context. The Institute started very small but with our first project—Quest to Learn—we found ourselves with a very big and very serious project on our hands. We were able to build a team around it, and soon we had learning strategists, former teachers, and education specialists sitting side-by-side with game designers.

With GlassLab, we now have a formal game development studio as part of the Institute of Play, bringing in people who are the best in the field of commercial game development. It’s been a fascinating trajectory. Our really tiny organization has grown to become incredibly diverse in the work we do and extremely interdisciplinary in the way we think. There are so many crazy, interesting organizations. In some sense, too, that’s the vision we have for the Quest schools and the work we do in informal learning—we aim to create vibrant environments for innovation and transformation of the way people engage with the world.

With the first class of 9th graders starting Q2L this month, what modifications will we see to the school’s staple curriculum?

When we first designed Q2L, we had a vision of what both the middle school and the upper school would look like. Middle school is a time when students are developing skills around what is means to be a systems thinker and understanding what tools they need to think systemically across disciplines. In the upper school, that systems thinking piece becomes embodied within a system citizenship framework. There is a big civic narrative in the upper school around why we care about systems thinking. It’s less about the mechanics of systems thinking and more about much broader questions of sustainability and self and the impact one has on his/her community. In the middle school, students use systems and design thinking as a way to analyze the world; in the upper school, they use those ways of thinking to make change in the world.

The upper school system mirrors that of a college model. The students work in semesters instead of trimesters. As kids move into 10th, 11th, and 12th grade, there are increased opportunities to take online courses. For the 12th grade, we have a vision around a very customized curriculum. We also have an early college program, which hopefully we will start to pilot in two years that allows 12th graders to take courses at The New School University. We hope that students have, by that point been supported in cultivating specific interests and can take a schedule of courses organized around those areas, as well as subjects that they are starting to think about studying once they enter college.

Has game design always been on your radar, or was it just something you happened upon?

It was never on my radar, although I do love to play. I was teaching interactive design at the University level when the Internet was just starting. The year was 1996, and I remember introducing Netscape Navigator to my students. It was a time when people suddenly began asking questions about new kinds of interfaces and ways of engaging users on screens. No one understood what it meant to design for the web because we didn’t have good models for interactivity at that time. Where do people click when they first visit a webpage? How do we keep them engaged? I started bringing traditional games, like Dominoes and Scrabble into my classroom to help students to answer these questions and to explore play as a strategy for design. I thought to myself, here are beautifully designed systems that are all about interactivity and engagement—if my students can figure out how these systems work, they’ll get ideas for what they can do with the web. I had a big ‘Aha!’ moment. Oh my gosh! Games are amazing! They are awesome! Here’s a totally transparent tool that shows off the very best of interactive design and the very human quality of play. I started to design games because I wanted to understand them better. I have always cared deeply about engagement and participation and what that can look like from a design perspective, so it seems natural to me that I ended up here.